SEE TOKYO THROUGH THE EYES OF ARCHITECT KENGO KUMA

World-renowned architect Kengo Kuma designs more than just buildings - his works serve as places where the past and present connect, and where visitors can experience Japan's history through a contemporary lens. We visited some of his most iconic projects in Tokyo, and learned the fascinating stories behind them from the man himself.

(This article was first published on the website Tatler Asia.)

- Kengo Kuma has a dream to restore Tokyo's landscape to its former glory.

"Historically, Tokyo was a city of wooden buildings," he muses. "After the war, we began building with concrete and steel which destroyed the beautiful culture of wooden buildings, and the sense of intimacy they created."

Named by Time Magazine in 2021 as the world's most influential architect, Kuma is taking inspiration from Tokyo's past to paint a landscape of the future. He is known for his use of natural materials to create contemporary spaces that enrich the connection between architecture, the natural world and local communities.

Kuma's work is experiential. Each project carries its own identity and, according to the architect himself, is "alive" - continually transforming and evolving in different light and through unique interactions of visitors passing through.

Following Japan's easing of border restrictions, we met with the world-renowned architect and visited some of his most iconic buildings in Tokyo.

Creating a Future for Tokyo's Past

Many of Kuma's works serve not as relics, but as reminders of the past and why it's crucial to protect it. Like the Meiji Jingu Museum, which was completed in 2019. In the building process, wood from trees felled during construction was used to make furniture and other elements inside the museum.

"The space was challenging, as it is in the forest," says Kuma. But rather than building against it, Kuma's design surrenders to the ancient woodlands that surround the sacred Meiji Jingu (Shinto shrine). "I wanted to make the building as low as possible, and in such a way that it disappears into the forest."

While the museum houses striking artifacts, including a carriage once used by Emperor Meiji dating back to the late 1800s, Kuma's design has turned the surrounding landscape into an exhibit in its own right. Large sections of the interior are deliberately left empty, with benches flanked by soaring windows that frame the stillness of the forest, presenting it as a work of art.

"In the 20th century, to build something monumental was the goal for many architects," says Kuma. "But now, the goal is to blend in. To become one with the environment."

Meiji Jingu Museum, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma

Meiji Jingu Museum, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma Meiji Jingu Museum, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma

Meiji Jingu Museum, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma Meiji Jingu Museum, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma

Meiji Jingu Museum, Tokyo, designed by Kengo KumaMany of Kuma's projects are connected to culturally significant landmarks.

In Shirokanedai, Kuma and his team redesigned the kuri within Zuisho-ji Temple, the first temple in Tokyo of the Obaku Sect, one of the Zen Buddhist schools brought to Japan by the Priest Ingen during the Edo Period.

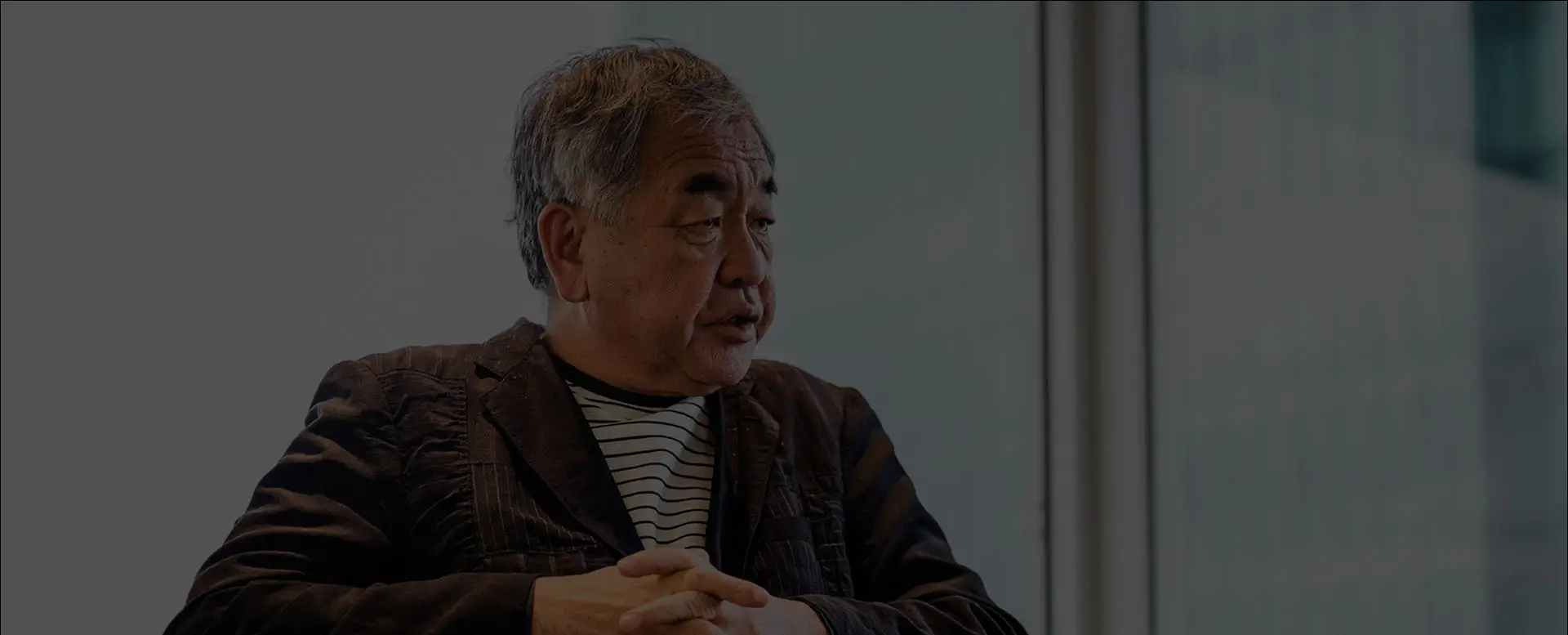

A U-shaped cloister featuring Kuma's distinctive wood slats was built on the south side of the axis, making the temple more accessible to the local community, who continue to use the space for worship and major family occasions.

At the center of the courtyard is a serene water pool with a raised stage, built to "encourage people to host events and performances for the community," says Kuma.

Zuisho-Ji, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma

Zuisho-Ji, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma Zuisho-Ji, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma

Zuisho-Ji, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma

Zuisho-Ji, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma

Further afield near Nagatacho, Kuma was commissioned for The Capitol Hotel Tokyu's extensive renovation in 2010. Here, he designed the hotel and its landscaping to blend seamlessly with the sprawling forest that encircles Hie Shrine. Located right next to the hotel, the shrine dates back to 1478.

"In Japanese, this is called shakkei, which means to borrow scenery," Kuma explains. "I wanted to borrow the beauty of the forest so that hotel guests can feel connected to the energy of the shrine. It is one of the unique things about Tokyo - that even in the center of the city, we have these peaceful sanctuaries."

At The Capitol Hotel Tokyu, Kuma's touch is felt from the moment you enter, with a traditional wood-grained intricate lattice design that frames the high-ceilinged lobby. Here, dramatic ikebana flower arrangements take center stage, changing regularly to reflect the theater of Japan's changing seasons.

"When designing hotels, one of the most important things is creating a connection between the neighbors and the guests," says Kuma, who has designed a dizzying number of hotels in Japan and around the world, including The Opposite House in Beijing and Ace Hotel Kyoto to name a few.

Capitol Hotel Tokyu, designed by Kengo Kuma

Capitol Hotel Tokyu, designed by Kengo Kuma©The Capitol Hotel Tokyu

Capitol Hotel Tokyu, designed by Kengo Kuma

Capitol Hotel Tokyu, designed by Kengo Kuma Capitol Hotel Tokyu, designed by Kengo Kuma

Capitol Hotel Tokyu, designed by Kengo KumaSince the 1970s, Shibuya has been the epicenter of Tokyo's youth culture. It's an electrifying pocket of Tokyo lit with flashing neon signs and home to the legendary Shibuya Scramble Crossing, where upwards of 1,000 people cross the multi-cornered intersection at a time.

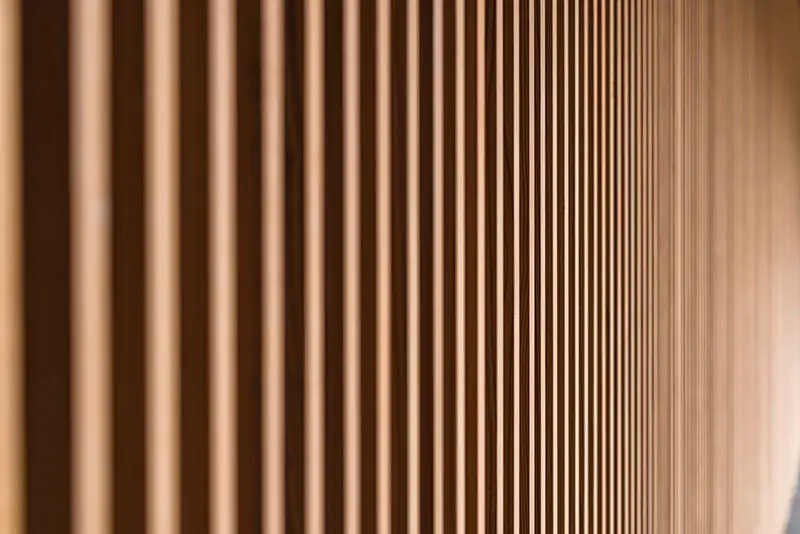

In the heart of Shibuya is Shibuya Scramble Square - one of Kuma's lesser-known but no less iconic works. One of his very few projects that doesn't use wood, the architect used aluminum mullions to create organic wave-like shapes. Forming a curvy curtain wall rather than sharp edges typically found on skyscrapers, they bring a softness to the bustling city center.

Shibuya Scramble Square, designed by Kengo Kuma

Shibuya Scramble Square, designed by Kengo Kuma©SHIBUYA SCRAMBLE SQUARE

Shibuya Scramble Square, designed by Kengo Kuma

Shibuya Scramble Square, designed by Kengo Kuma©SHIBUYA SCRAMBLE SQUARE

Shibuya Scramble Square, designed by Kengo Kuma

Shibuya Scramble Square, designed by Kengo Kuma©SHIBUYA SCRAMBLE SQUARE

Reimagining Tradition

Kuma also brings his penchant for nostalgia to more contemporary concepts. Like at Pigment Tokyo, a store for artists in Shinagawa, where the ceiling is brought to life with a wave-like structure constructed from Kuma's signature bamboo slats.

Much more than an art supply store, Pigment positions itself as a hub for artists, and a custodian of sorts for ancient knowledge and tradition to be passed on to future generations of artists.

The striking back wall is lined floor-to-ceiling with glass jars containing a spectrum of powdered pigments, including iwaenogu - pigments made from finely ground natural materials like coral and crystals such as onyx and malachite. When mixed with a paint medium like animal glue, it becomes a highly saturated paint with an incredible vibrancy and naturally-occurring sparkle.

Pigment Tokyo is also home to a museum-worthy collection of brushes, made from a plethora of unique materials including sable hair and even chicken feathers. For a chance to experience this rare style of painting, in-store workshops guided by professional artists can be arranged.

Pigment Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma

Pigment Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma Pigment Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma

Pigment Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma Pigment Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma

Pigment Tokyo, designed by Kengo KumaNakameguro is the best neighborhood in Tokyo for enjoying sakura season in the spring. During this time, the riverside promenade is blanketed in a canopy of blush-pink cherry blossoms, and the streets are lined with locals and visitors alike who gather under falling petals to enjoy the scenery.

Sitting on this riverfront is Starbucks Reserve® Roastery Tokyo, a four-story Mecca for coffee lovers, partially designed by Kuma, whose soothing lightwood exterior emits a welcoming and gentle presence in the lively neighborhood. Inside, look carefully and you'll find charming nods to Japanese culture, including an origami-inspired ceiling and small planters that Kuma interpreted as modern bonsai.

As well as coffee, Starbucks Reserve® Roastery Tokyo celebrates Japan's historical love for tea with a Teavana tea bar, where customers can choose from a selection of loose-leaf teas and creative tea-based beverages.

Also housed in the building is Princi®, an artisanal Italian bakery founded by Italian baker Rocco Princi, which first opened in Milan in the 1980s. The aromas are intoxicating, with freshly baked goods on offer like bread, cornetti, pastries and pizzas for an authentic taste of Italy.

On the third floor is a bar with a wraparound terrace - where better to enjoy a Starbucks Reserve Espresso Martini?

Starbucks Reserve in Nakameguro, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma

Starbucks Reserve in Nakameguro, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma©STARBUCKS RESERVE® ROASTERY TOKYO

Starbucks Reserve in Nakameguro, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma

Starbucks Reserve in Nakameguro, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma©STARBUCKS RESERVE® ROASTERY TOKYO

Starbucks Reserve in Nakameguro, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma

Starbucks Reserve in Nakameguro, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma©STARBUCKS RESERVE® ROASTERY TOKYO

"Every Building is a House"

"To me, every building is a house. No matter the nature of what I'm designing - when I design a museum, for example, a museum is a house, a home for art and a place for people to come, relax, enjoy," says Kuma. "The neighbors are important to consider, too, and by neighbors I mean the hills, rivers, buildings and people around us. Wherever we are building, it's important to us that we become a friend to the area."

Kuma grew up between Yokohama and Tokyo in a satoyama - a name given to Japan's mountain villages that coexist in harmony with nearby forests and mountains.

"It was a one-story house with tatami floors and walls made of clay. It was an intimate space, and I still dream of my time in that house. It remains my idea of a perfect home," Kuma muses, fondly recalling days spent reading under the afternoon sun on the engawa - a boarded floor extension that runs along the side of traditional Japanese-style houses, typically facing a garden.

Tokyo's Coolest Neighborhood

Today, Kuma resides in Kagurazaka, a quaint but stylish neighborhood near Shinjuku. "It has a unique topography with narrow streets and hills. I like that it has a village atmosphere," says Kuma.

Once a lively Geisha district, it is now one of Tokyo's most fashionable and interesting pockets, where tree-lined streets and charming alleys lead to countless hidden gems - from cool restaurants and izakaya to fine dining, and chic bars that serve everything from small-batch sake to ornate seasonal cocktails.

It is also known as Tokyo's "Little France," where you'll find authentic French bistros and some of the best bakeries in a city that's already known for its stellar baked goods. For a casual meal, Kuma enjoys popping down to Le Bretagne, a hidden gem tucked away from the main road which serves buckwheat crepes. "I call them soba crepes," says Kuma. "The owner is from Normandy and his wife is from Japan, so it's French cuisine but with some Japanese flavors."

For special occasions, one of Kuma's favorite restaurants is the three Michelin star Ishikawa. One of the few ryotei-style restaurants remaining in the Kagurazaka area, Chef Hideki Ishikawa is passionate about keeping the tradition of kaiseki alive.

"He has created a real sense of place in his restaurant," Kuma praises.

Japanese architect Kengo Kuma in his Tokyo office

Japanese architect Kengo Kuma in his Tokyo officeHeart of the City

Sense of place is the foundation on which Kuma builds his masterful designs. Whether it's connecting the past with the present, or bringing city dwellers closer to nature.

Japan National Stadium, which Kuma and others designed for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games, is a pagoda-inspired building with eaves made of wood sourced from Japan's 47 prefectures, with a lush exterior covered with various plants. Inside, the large open roof resembles the opening of a forest canopy, and the 67,750 seats are deliberately colored to look like leaves falling to the forest floor - with lighter shades cascading down into deeper hues of green and auburn.

"It's located within Meiji Jingu Gaien, which I know very well, as I am a member of a tennis club there and I always enjoy walking in the park. I didn't want a big concrete box in my favorite park," he says, laughing. "So I designed the stadium in a way that feels like part of the forest."

The Japan National Stadium, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma

The Japan National Stadium, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma The Japan National Stadium, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma

The Japan National Stadium, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma The Japan National Stadium, Tokyo, designed by Kengo Kuma

The Japan National Stadium, Tokyo, designed by Kengo KumaAs he tells me this, we are sitting in Kuma's Tokyo office, which has views looking out to Japan National Stadium. He takes a thoughtful pause, then states, "Sometimes, great design can destroy a city. Famous architects have tried to create architectural monuments…but after Covid-19, it's clear that such things are no longer necessary. Covid-19 has changed our cities... and that change is only just beginning. People are finally understanding the importance of the community you belong to, the importance of nature and the way we live amongst it."

Taking the time to view Kuma's works, to observe their subtle yet significant standing in Tokyo's urban landscape, it's easy to see that the legacy he hopes to leave behind is not necessarily his own. Instead, Kuma's works facilitate a deeper understanding of one of the world's oldest and most fascinating cultures, with the hope that they will help preserve it for generations to come.

"In the end," he says. "I will always believe that good, humble design is better than great design."