UNCOVER JAPAN THROUGH THE ARTS OF UKIYO-E

Explore and immerse yourself in the role that the art of ukiyo-e and kabuki had and continues to have in Japanese culture and arts. Learn about ukiyo-e from a Japanese expert in addition to experiencing the amazing makeup of kabuki, one of Japan's most endearing and fascinating performing arts.

Japan’s Edo period (1603–1867) was characterized by huge economic growth — and with that new-found affluence came contemporary forms of entertainment such as ukiyo-e, a school of art that depicted subjects from everyday life.

Such was the popularity of ukiyo-e that its impact can still be seen on a visit to Tokyo, where it’s possible to enjoy a related experience offered by Shinnichiya in various locations. The program comprises an introduction to ukiyo-e led by Ms. Akiko Moriyama, a researcher of Edo culture, followed by an experience in the makeup of kabuki, a traditional drama with highly stylized song, mime, and dance.

Although ukiyo-e is known mainly for its woodblock prints, the genre includes paintings. “E” literally means “picture,” while “ukiyo” refers to the pleasure-seeking urban lifestyle and culture of the time. This was largely thanks to the Edo Period being a time of prosperity and relative peace. As Ms. Moriyama explains, “ukiyo-e depicts all the pleasures of the people of Edo.”

Ukiyo-e originally focused on portraits of beautiful women and actors, and yakusha-e (actor prints) were very popular. Later, landscapes also became beloved subjects.

The artwork was not reserved for the upper classes, as a painting only cost the same as a bowl of soba noodles, a popular and affordable dish of the time. Furthermore, rather than being framed or hung up, one would simply hold the painting in one’s hands for casual viewing. The rare ability to hold authentic ukiyo-e prints during the program offers a window into how people in those days would have appreciated this art form.

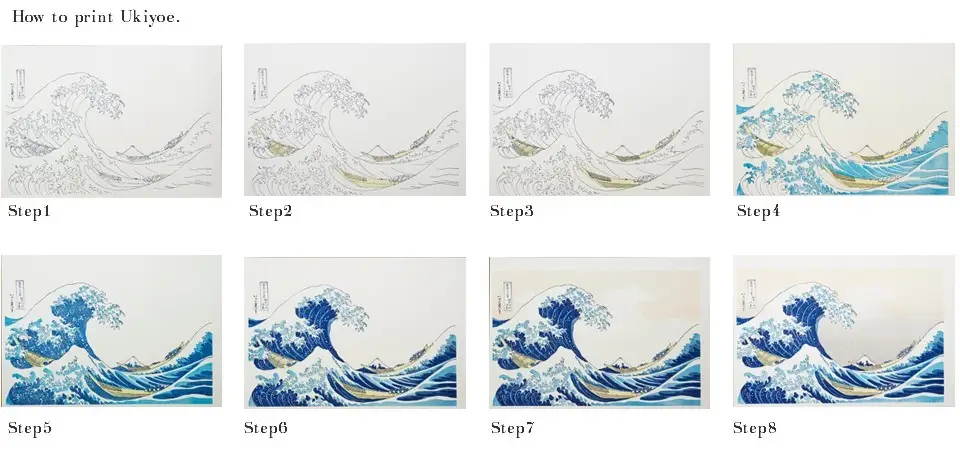

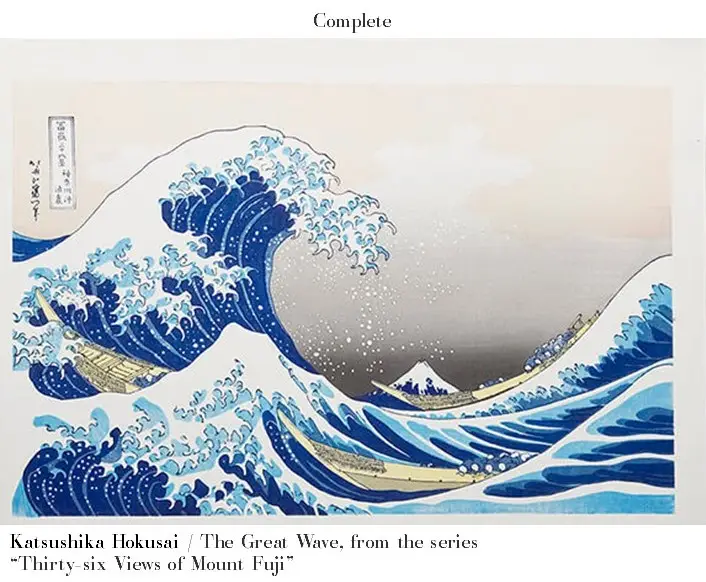

Despite the genre’s accessibility, the paintings took a team of craftsmen to create. Artist called (e-shi), such as the famed Hokusai Katsushika, would sketch the design before engravers (hori-shi) would carve it out to create woodblocks (one for each color to be featured). Next, printers (suri-shi) would apply the pigments and dyes to each woodblock in turn, placing Japanese washi paper on top each time by using markings to ensure each color was in the correct place. The colors were applied in order from the lightest to darkest and from the smallest area to largest area, with gradations added as a finishing touch to create each ukiyo-e.

After its boom within Japan, ukiyo-e’s popularity continued abroad, particularly after the opening of the country’s ports in the mid-nineteenth century. The art sparked interest among Western European artists, and its popularity and influence is often referred to as Japonisme.

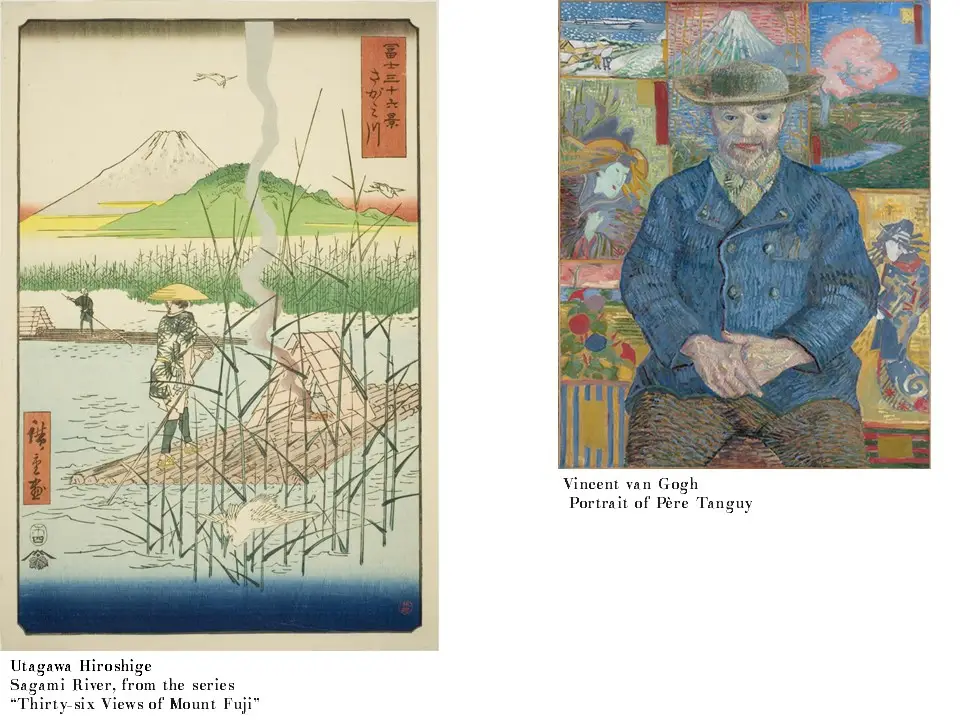

We can see Japonisme in the work of several famous artists, such as Vincent Van Gogh’s “Portrait of Père Tanguy.” Behind the subject is a number of ukiyo-e as Van Gogh saw them. He so loved the art that he once wrote in a letter: “All my work is based to some extent on Japanese art.”

On closer viewing of the painting, it’s possible to identify the image of Mt. Fuji from the Sagami River, which is part of a series called Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji by Hiroshige Utagawa. The painting on the right (or Tanguy’s left) is of an oiran, a high-ranking courtesan, while the image on the left depicts a male actor who played a female role in kabuki, as women did not hold roles in the theater.

Kabuki, is characterized by spectacular performances with extravagant costumes and elaborate kumadori makeup. Kabuki is often depicted in ukiyo-e, as it was an accessible form of entertainment in everyday life at that time.

One example is Utagawa Toyokuni III’s “Flourishing of Edo Pictures Depicting Dances.” It shows the interior of a crowded playhouse in Tokyo’s Asakusa district during the Edo period. On the elevated walkway (hanamichi) leading towards the stage stands the main character, Shibaraku. His name, which he calls out on his appearance on the elevated walkway, literally means “wait a moment” as he halts wrongdoing and rescues people.

Utagawa Toyokuni III

Utagawa Toyokuni III

Flourishung of Edo Pictures Depicting Dances

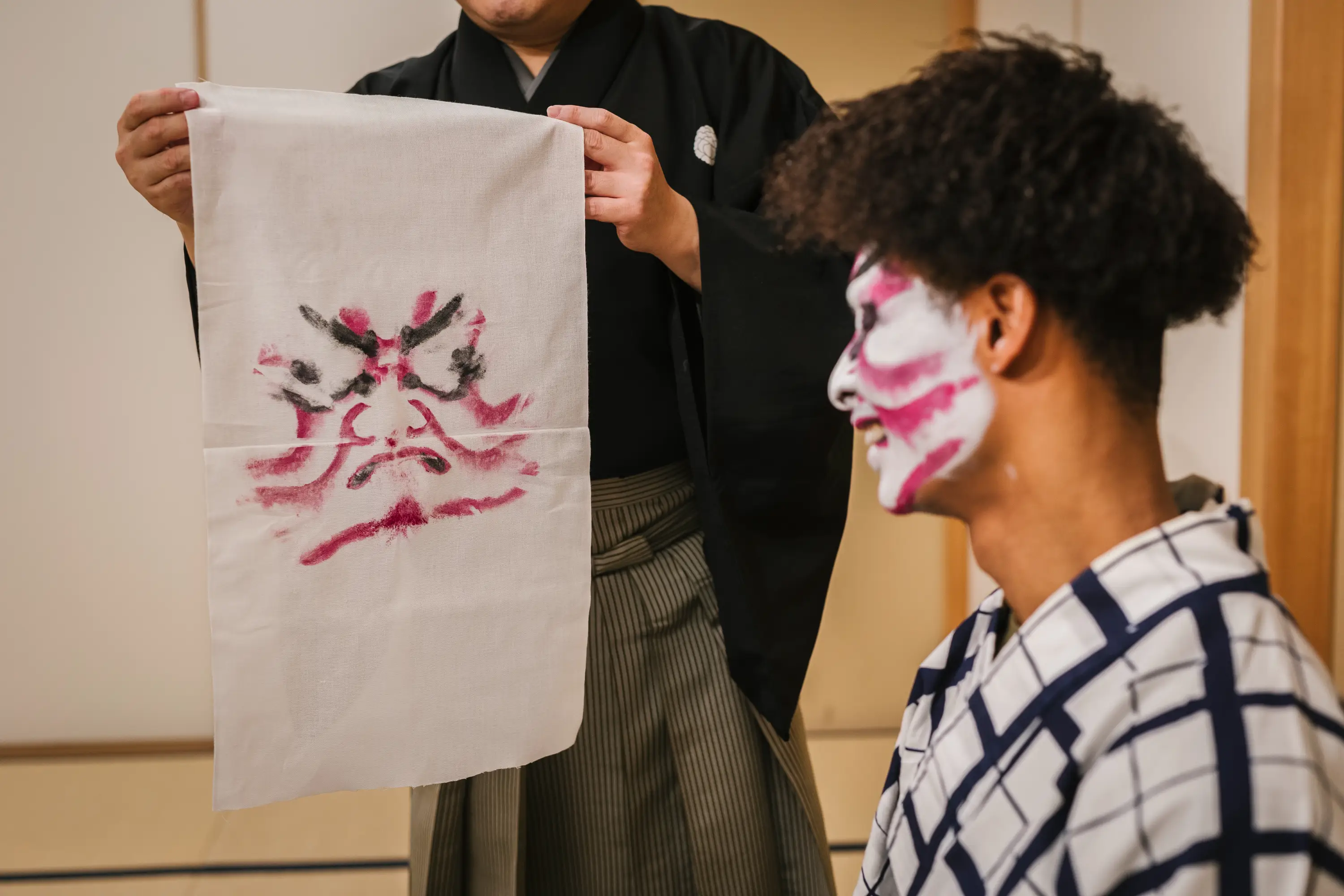

Shibaraku wears eye-catching white and red kumadori makeup called sujiguma to match his heroic role. This sujiguma makeup is the most flamboyant of kumadori , its red lines expressing the actor’s vigorous sense of justice and dynamism.

To step in the shoes of a kabuki actor, why not opt to have your face painted in this style?

This time, participants experienced "kumadori ," a process of applying paint to the face by Mr. Shijuro Tachibana, a kabuki instructor.

You can even have a souvenir of the experience to take home thanks to oshiguma. This practice involves gently pressing a cloth on the face after a performance as a copy of the makeup’s appearance. Alternatively, you can opt to watch the face of a kabuki actor be painted.

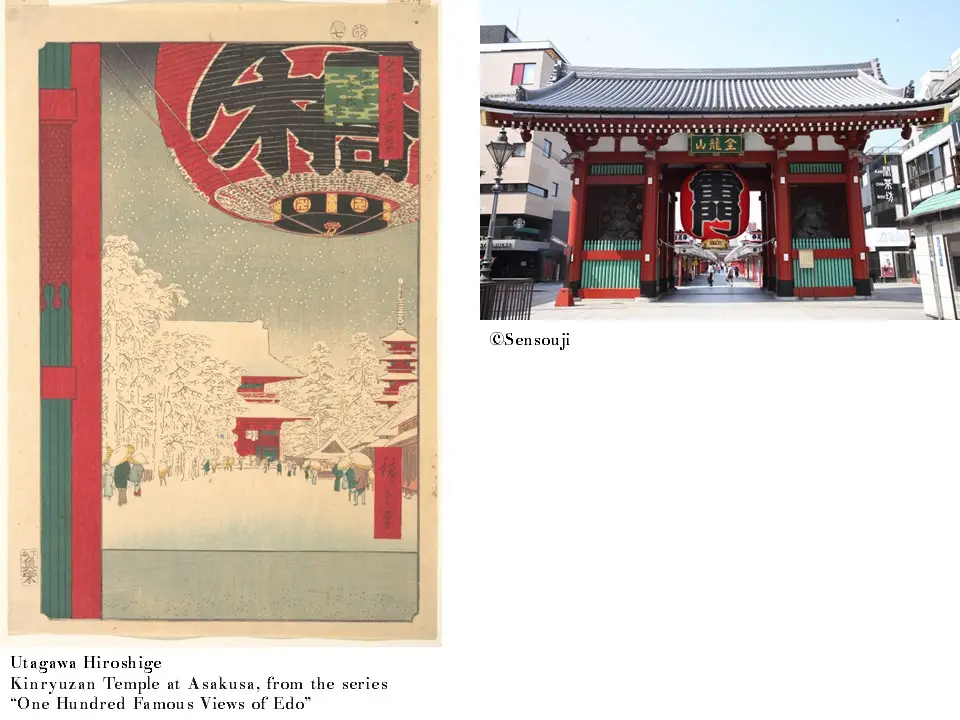

Some of the places depicted in ukiyo-e prints can still be seen in and around Tokyo, so it’s possible to look out for them while exploring. They include Kinryūsan Sensoji Temple at Asakusa, a building that features in the series “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo”.

Japan’s Edo period brought forth a wealth of art that can still be enjoyed today. So why not take time to uncover the artworks and their history while learning firsthand about some of the entertainment of such a prosperous time.

*The experience introduced in this article is a special arrangement by Shinnichiya.

Please contact the email below for more information.

Contact:

Shinnichiya

reservation@shinnichiya.com